Helping Children in Distress with Psychological First Aid

Children face many different challenges as they grow up. Just as adults experience a range of emotions and circumstances in their lifetimes, kids experience joy, laughter, sadness, grief, and indeed stress at varying moments throughout their childhood.

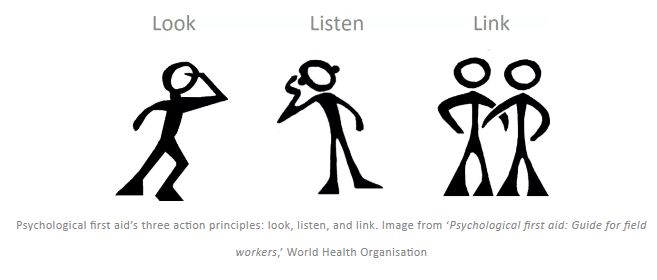

Throughout the highs and lows of a child’s emotional and intellectual development, parents must be prepared to react appropriately and nurture healthy emotional responses. It is important to remember that children are not ‘little adults’ and often require support that grown-ups do not due to their dependency on others for protection and care. Our kids don’t have the same life experience or emotional maturity that we adults do, and because of this they react to and understand stressful experiences differently. Our unconditional support is what allows our children to flourish on their own later in life, particularly when encountering difficult challenges and stressors.

At this moment in time, our young learners are likely to be experiencing relatively high levels of stress and concern. By paying close attention to wellbeing and applying a few psychological first aid methods, parents and caregivers can provide their children with the appropriate tools to cope with this challenge - and any other they encounter in future.

What is psychological first aid?

When terrible things happen to people in our communities, countries, and the wider world, it is our natural human instinct to reach out a helping hand. Psychological first aid (PFA) offers a method of helping people in distress so that they feel calm and supported in coping with their challenges.

PFA is an adapted and alternative form of "psychological debriefing” that is recommended by many international expert groups, including the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and the World Health Organisation (WHO).

PFA offers humane, supportive, and practical assistance to people who have recently experienced a serious stressor. Simply put, it is a direct response and set of actions to help someone in distress. PFA for children is used to reduce the initial distress kids may experience as a result of accidents, natural disasters, or conflicts.

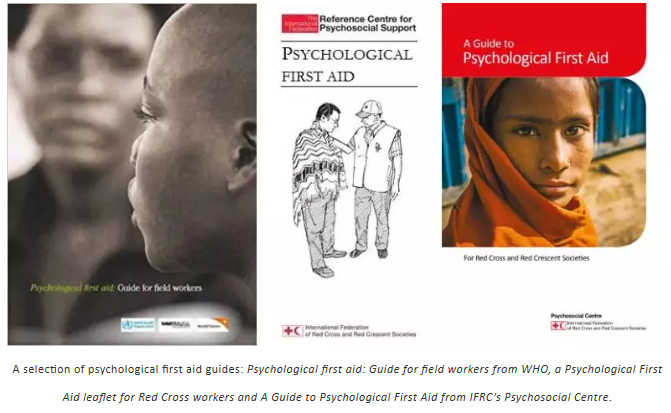

There are three action principles underlying PFA: look, listen, and link. Originally presented by WHO, World Vision International, and the War Trauma Foundation in their book Psychological First Aid: Guide for field workers, these action principles are designed to guide practitioners to assess and safely enter a crisis situation, approach affected people and understand their needs, and link them with practical support and information.

Almost all PFA providers use the ‘look, listen and link’ principles in their training manuals and materials, including IFRC and Save the Children. The following section describes each principle in more detail:

01 Look

Crisis situations can change rapidly, and it is always important to “look” around you before providing help. The action principle ‘look’ reminds a helper to:

- Look at your surroundings and check for safety

- Look for people with obvious, urgent basic needs

- Look for people with serious distress reaction

One of the groups most likely to need special attention during a crisis or stressful situation are children and adolescents, and as such it is important that the people in their lives are always looking out for them.

02 Listen

Listening to the person or people you are helping is key to properly understanding their situation and needs, helping them feel calm, and offering appropriate assistance. The action principle ‘listen’ refers to how the helper should:

- Approach people who may need support

- Ask about people’s needs and concerns

- Listen to people, and help them to feel calm

Often people who experience a crisis or otherwise stressful situation may feel anxious, upset, confused, or overwhelmed. For parents and caregivers helping their children feel calm, the most important aspect of the ‘listen’ principle is to remind them that you are there to help – you will keep them safe.

03 Link

Linking people with practical support is a key function of PFA. Although every situation is unique, helping people to help themselves and regain control is what will help them recover in the long term. The action principle ‘link’ directs a helper to:

- Help people address basic needs and access services

- Help people cope with practical problems

- Help people gain access to information

- Link people with loved ones and social support

It has been shown that people who felt they had good social support following a crisis were able to cope better than those who felt they were not well supported. Linking people with loved ones and social support is a vital component of PFA and holds especially true for children and adolescents.

How can we apply psychological first aid methods to help children in distress?

A child's response to an emergency or crisis is highly influenced by their experience of the event first-hand. However, a child’s response is also influenced by how caregivers and others around them react to the event and to the child. Children react according to what they understand of the situation, which in turn is related to their stage of development.

Understanding common reactions to stressful situations during different developmental stages can be helpful for parents and caregivers when identifying a child in distress. Common reactions to distressing events linked to a child’s age are described in the IFRC Psychosocial Centre’s A Guide to Psychological First Aid, as well as recommended responses for adults applying PFA methods to support children during these times. Detailed below:

Infants (0-2 years)

Infants of up to two years have little or no understanding of the meaning or consequences of a stressful event, but they are very sensitive to differences in the reactions and behaviour of their parents or caregivers. Infants are not able to clearly identify or articulate what they need by speaking, but they do demonstrate distress through their behaviour.

Common reactions of infants in distress include being clingier with parents and caregivers; experiencing changes in sleeping and eating patterns; crying more and being more irritable; being afraid of things they weren’t previously afraid of; becoming hyperactive or losing concentration faster; and changing the way they play (e.g. less/more often, repetitively, more aggressively, etc.).

If your children are displaying any of the reactions or changes in behaviour noted above, you should:

- Keep them warm and safe

- Give cuddles and hugs

- Keep a regular feeding and sleeping schedule, if possible

- Speak in a calm and soft voice

- Keep them away from loud noises and chaotic situations

Young children (2-10 years)

Children aged two to ten years can express themselves better with language, although in the younger years they still have a limited understanding of the world outside their own personal experiences. Between ages two and six children do not quite understand the consequences of stressful events and emergencies. From ages six to ten children develop their understanding of how things are linked together and of cause and effect (i.e. China is dealing with a public health emergency -> schools have been closed to prevent further risk to children’s safety). In this age group children are interested in concrete facts and have a better understanding of death and loss, although they often struggle with drastic change.

Common reactions of children in distress in this age group include being clingier with parents and caregivers; regressing to younger behaviour; experiencing changes in sleeping and eating patterns; withdrawing from social contact with others; becoming hyperactive or losing concentration faster; being more irritable, aggressive, or restless; and experiencing physical reactions such as headaches, stomach aches, and muscle pains.

If your children are displaying any of the reactions or changes in behaviour noted above, you should:

- Give them extra time and attention

- Keep to regular routines and schedules as much as possible

- Explain to them that they are not to blame for bad things that have happened

- Provide a chance to play and relax, if possible

- Give simple answers about what has happened, but don’t include frightening details

- Allow them to stay close, if they are afraid or clingy

- Remind them often that they are safe

- Be patient with children who start behaving as they did when they were younger, such as sucking their thumb or wetting the bed

- Avoid separating young children from their families

Older children and adolescents (10-18 years)

Teenagers have an increased understanding of other people’s perspectives; they understand the seriousness of crisis or stressful situation and how it affects them and others. Teenagers start to feel a strong sense of responsibility for themselves and their families. Establishing their identity in relation to others and develop a more engaged social life becomes of increasing significance to teenagers, with friends being as important and supportive, or even more so, than parents or family when dealing with a crisis or stressful situation.

Common reactions of teenagers in distress are more like those of adults. At this age they feel intense grief, self-consciousness, or guilt and shame when they were unable to help people who have been hurt. Teenagers can show excessive concern about others or become self-absorbed and experience feelings of self-pity. Changes in their relationships with others may push them to start taking risks and engaging in self-destructive or aggressive behaviour.

If your children are displaying any of the reactions or changes in behaviour noted above, you should:

- Give them your time and attention

- Help them to keep regular routines

- Provide facts about what happened and explain what is going on now

- Allow them to be sad, don’t expect them to be ‘tough’

- Listen to their thoughts and fears without being judgmental

- Set clear rules and expectations

- Ask them about the dangers they face, support them and discuss how they can best avoid being harmed

- Seek out opportunities for them to be helpful

Please keep in mind that all children develop at different rates, and some children may require varying levels of support (i.e. from a slightly younger or older age group) during times of stress. This is normal.

Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable during times of crisis or increased stress. Stressful events can disrupt the otherwise-familiar world around them, impacting the people, places, and routines that make them feel secure. Family networks and other caregivers are important sources of emotional support for children, particularly when they are dealing with difficult situations or emotional challenges.

It is common for children to continue functioning socially and to play, smile, and laugh, whilst their feelings of distress are communicated in other ways (e.g. through drawings, change in appetite, disrupted sleeping patterns, etc.). Because of this, parents and caregivers should check in on their children regularly about their feelings and thoughts during times of stress.

Parenting can be difficult during times of crisis or stress. Together, we can overcome anything that life throws our way.